Six Years Since the Valley Fire

Greetings, beloved community!

I know most of these recent posts have been health updates, and many of you have reached out inquiring about how last week's CT scan and conversation with my doctor went. Thank you for caring!

It feels like the scan yielded good news, with the slight caveat that I am not yet out of the woods entirely and appear to have some uphill climbing yet to do. I've received some pretty major downloads between last week's scan and doctor visit, and a follow-up with yet another physician this week, and I am in the process of integrating it all. I look forward to sharing more in the coming days!

In the meantime, however, last weekend marked some pretty important anniversaries. Not only has it been 20 years since the 9/11 attacks (and the birth of my wonderful nephew Alec the very next day); it has also now been six years since the Valley Fire razed much of my Cobb Mountain community to the ground, displacing me and my family from Lake County and serving as a major chapter break in my life.

To mark the occasion, I’m sharing this amazing short documentary about our grassroots response to the fire at KPFZ 88.1 FM, the community radio station where I served as host of the weekly Wake Up and Thrive and accidental initiator of the round-the-clock coverage that helped our local community survive and grieve the disaster.

The film, Fire Station 88.1, created by Boston Picture Group’s Marnie Crawford Samuelson and Shane Hofeldt, can be viewed for free on my YouTube channel. Our emergency response work at KPFZ was also featured on BBC Radio and in the Los Angeles Times.

When that epic conflagration hit in the summer of 2015, it was among the largest and most destructive wildfires on record in California. It was a time before “fire season“ was such a common term in our shared vocabulary here. It in many ways heralded a new era of climate-change-fueled disasters in the American West and beyond.

Two years after the Valley Fire, the 2017 Tubbs Fire resulted in my family’s evacuation (this time temporary) from Santa Rosa, CA, while the Thomas Fire in Southern California claimed 23 lives. The following year, the 2018 Camp Fire became the largest wildfire on record and scarred all our memories as it leveled the town of Paradise, CA, while the nearby Mendocino Complex Fire burned for over three months and filled the air with smoke, forcing countless evacuations, and triggering in many of us NorCal denizens a sort of post-traumatic stress response and the dawning realization that this could very well just be our new reality.

Since then, the end of each summer has brought with it not only the familiar lament of students and teachers returning to school and once again needing to set the alarm, but a new concern heard on the lips of many: I hope fire season isn’t too bad this year.

The Valley Fire happened at a significant time in my personal biography. That spring, I had journeyed to Washington DC, where I resolved to run for United States House of Representatives. When the fire broke out, I had not yet declared my candidacy. I was just beginning to prepare for the campaign ahead.

It was a hot and remarkably windy day in the kingdom of Cobb Mountain, when I took my dog Phoenix for a walk from my home in the rural, alpine hamlet of Loch Lomond.

“A very windy day,“ I remember thinking repeatedly as we made our way home through the nearby forest.

My other dog at the time, Spirit, was not with us. She had just gone missing a couple of weeks earlier.

The place I was renting in Loch Lomond had a beautiful redwood porch out back, overlooking a large uninhabited stretch of forest leading into a piney valley and up the north face of Boggs Mountain.

I looked up to see what was initially naught more than a distant plume of smoke arising from what looked to be the adjacent community of Cobb.

One of the things that stands out to me most recalling the story is how very quickly things went from, “wow that sure is a big plume of smoke in the distance,“ to, "holy shit, there is a tremendous wall of smoke and flame rapidly advancing in my direction."

That whole process took about ten minutes.

Nowadays, best believe I have go bags — one in the car, and another two in the garage — but back then, this wasn’t part of my consciousness. I threw some clothes and a couple of other essentials in a duffel.

Then, as I prepared to take my leave, I got a Facebook message from my friend Craig, who was stranded without a vehicle further up the mountain and closer to the flames. I told him to start walking toward me and I rolled out to pick him up along with his dog, Boogie.

By the time I made it to their neighborhood, roads leading in were blocked by emergency vehicles and I had to persuade firefighters and police at two checkpoints to let me through. Spot fires were breaking out all over the place and the main wall of flame was directly visible as it advanced on us. (Weeks later, when roads reopened, I would see the ashy remnants of this entire neighborhood, which had burned completely to the ground.)

After I picked up Craig, now more than painfully aware of the emergency situation we faced (as well as the precise distance of the approaching blaze), I sensed that we had time to make a quick stop at my house. I grabbed my computer, hard drive and physical photos, my trunk full of writings then known affectionately as the "dox box," and my guitar.

I remember interacting with some of my neighbors in the driveway as we all made our collective exit from the imperiled neighborhood. There were no sirens going off, no authorities telling us to go, no text alerts — just a shared intuitive sense that danger was approaching and it was time to move.

As I exchanged phone numbers with a few of my neighbors, I recall thinking it ridiculous that I somehow hadn’t already done this, and that we had never come even remotely close to talking about what we'd do in the event of a wildfire or other emergency.

In the months and years since the fire, this experience led me to become a certified first responder and ultimately to write articles and lead workshopson emergency preparedness and community resilience.

As we got underway, we stopped briefly at the general store, where several locals were congregating, just to make sure everyone had a ride down the mountain. Then, Craig, Boogie, Phoenix and I exited the burning landscape.

Our first stop was in Lower Lake, to top off my gas tank and get a few gallons of bottled water. Then we headed to nearby Kelseyville, where my dear brother Ian had a safe space to rally, far from the flames. On the way there, we stopped on the side of the road to take a picture of the now massive cloud of gray fumes beginning to obscure most of the sky to our south, thinking, "my home and all my possessions could very well be among those molecules of smoke and ash."

I should mention here that Satya and her mother Alaina were, fortunately, in Ohio visiting family when this whole episode took place. This freed me up during the emergency to think more about others.

During the Tubbs Fire incident in Sonoma County two years later (with us all living in Santa Rosa, Alaina residing just a few blocks away from me in the downtown area), when I woke to an early-morning war-zone of smoke and the rising of a red rising sun we’re now all too familiar with here on the West Coast, it was all I could do to get my child out of harm’s way. I already had a go-bag packed, and within ten minutes I was picking them both up and driving us all to my mom’s house on the cool, moist coast south of San Francisco, a world away from the unfolding disaster.

With Satya safely out of harm's way during the Valley Fire, though, my instinct was to stay close and see what I could do to help out. But first we had to get to safety and reassess the situation.

We arrived at Ian's house, began to share our tale of evacuation, and made some calls to check in with our loved ones. Then, as our friend Danielle warmed up some soup, we turned on the radio and tuned in to KPFZ, Lake County's locally treasured community radio station, where the variety show I hosted aired every Tuesday.

As the sun went down and an historic fire was raging through Cobb, there was a rerun on the air. We realized that the programmer who was usually on at this time lived in Cobb and had probably evacuated as well. The emergency was just beginning to unfold, and we imagined that people all around the lake were curious what was happening on Cobb. Folks everywhere were likely tuning in for information, only to hear a repeat of last week's reggae show.

I had the keys to the station. We all knew instinctively what to do.

We loaded up, drove to Lakeport, entered the empty broadcasting booth, and began reporting. We monitored the CalFire website, tracked the scanner and social media pages, and shared everything from road closures and the extent of fire spread to the locations of evacuation sites and how to find resources. We took calls and facilitated a community dialogue, both logistical and spiritual, that transmitted essential information, honored all voices, and lasted all night.

We ran the boards for hours on end, emerging from the radio station bleary-eyed and bedraggled in the morning, when we were relieved by some other programmers. Thus began KPFZ's 24/7 coverage of the fire, which went on for weeks.

We worked out a new schedule with other programmers that accounted for every hour, and our ragtag crew that began the coverage remained in the booth most nights during the prolonged emergency. Especially in those first few days of the radio response, something truly sacred was happening. We would take calls from volunteers at one evacuation center saying something like, "we are staging evacuated horses here at the Moose Lodge, but we've run out of feed!" — and two minutes later, we'd have another caller saying, "I'm now headed to the Moose Lodge with a truckload of feed."

Some callers would phone up to share words of hope and encouragement, or to express appreciation for first responders. Some would cry and lament having lost everything. Some shared the latest firsthand info on where the fire front was moving as it crossed roads and continued to spread. Some callers updated listeners on what supplies were needed at evacuation sites, and where volunteers were needed most. Others still would share where evacuees could receive their mail, or find clothes and food, or access free childcare and healing services.

On that first night, we began the Valley Fire Info Database, a Google Doc freely editable by anyone (and abused by no one), to compile the data that was streaming in from all angles. Within two days, we were printing copies of the document and handing them out to displaced people at the several evacuation centers that had sprung up at churches, schools and other gathering places around the county. People received the document with tears of gratitude streaming down their cheeks. It would be another several days before the local emergency management authorities had any meaningful printed information to put in their hands.

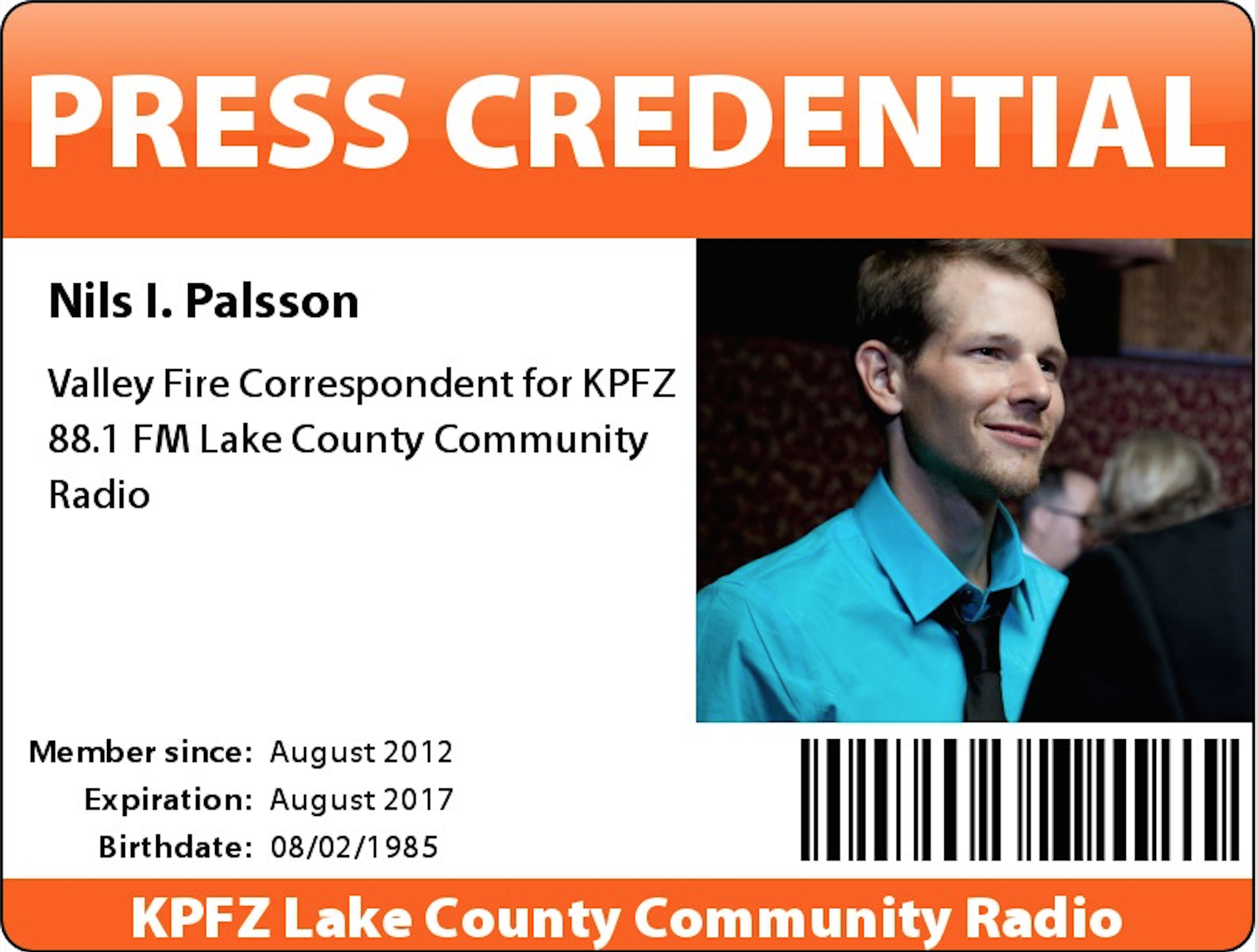

Some days, my friends and I reported from the field. We went around to relief shelters to see what kinds of needs were out there and phoned them in to the station. We created press badges for ourselves and used them to get into the burn zone, then we reported on which neighborhoods had been leveled, which were still standing, and which had partially burned.

While I was blessed to have local hospitality including a sofa to sleep on and food to eat at Ian's house, I spent many evenings hanging out and interacting with other fire refugees (many of them much worse off than me) at local relief shelters, where people of all ages were sleeping in cots, eating canned food, and doing their best to coexist in large numbers without any real privacy. I remain humbled by the strength of spirit exhibited by these resilient human beings, who faced the uncertain situation with humor, grace and love.

Under Ian's direction, we organized live music events at some of the relief shelters, including a concert at the aforementioned Moose Lodge just a couple of nights into the disaster. I used to occasionally play drums and sing with Ian and Danielle's reggae band, Righteous Vibrations. And I'll tell you, I have never seen anyone dance as freely and powerfully as some of those evacuees who had just lost everything.

That night, Ian and I spent some time in the parking lot, talking with (and ministering to) some of the displaced folks who had lost everything.

One man had gone to bed the night the fire broke out, thinking he was safe several miles from the blaze. He was awoken in the middle of the night to a rapidly advancing wall of fire, just narrowly escaping with his wife as their home (and their son's home next door) went up in flames. He was a rancher who had to leave behind 180 head of cattle, and the following day he was escorted down the closed road by emergency personnel to check on his animals. They had all survived by getting into the pond that night. (Water is life.)

The rancher began to cry as he described what had happened when he went to feed them. Normally at feeding time, he said, the stronger and larger "alpha" animals would bully the little ones, shoving them aside with their massive horns, guarding the feed trough so they could get as much food as possible. In the wake of the fire, however, these larger animals graciously stepped aside, gently helping to direct the herd so that each member got enough to eat.

In the numerous natural disasters I've now experienced, I've witnessed similar behavior in humans. These disruptive situations actually bring out the best in us. This theme is explored eloquently in Rebecca Solnit's book, A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster. "Just as many machines reset themselves to their original settings after a power outage," she writes, "human beings reset themselves to something altruistic, communitarian, resourceful and imaginative after a disaster."

Celebrated sociologist Enrico Quarantelli came to similar conclusions after spending decades studying and interviewing thousands of people in such crises. As his 2017 New York Times obituary describes, "Quarantelli and his colleagues discovered that virtually everyone acted rationally, even generously. They protected one another. They rushed to look for survivors. There was no traffic jam to frantically flee the disaster area; the traffic coming in, to help, was worse."

The eulogistic article continues:

“In general,” Quarantelli and Dynes wrote in 1975, summarizing their findings, “cooperation rather than conflict is encouraged.” Hysteria was largely mythical; actions mistaken for panic, like running, en masse, as fast as you can from a collapsing building, were actually reasonable responses to danger. “Natural disasters democratize social life” and “strengthen community identification,” they wrote. Class distinctions disappear, at least temporarily, as people suffer and work together. Looting is exceedingly rare, while fears of looting are rampant. Government bureaucracies, which are designed to be rigid and dependable, not to improvise or adapt, are often left rudderless. But ad hoc groups of ordinary citizens arise to pick up the slack. The center’s sociologists observed these “emergent organizations” forming again and again after disasters around the world: teaming up and switching on, like a kind of civic immune response. Victims of disasters often wind up with heightened feelings of kinship and purpose. A mentor of Quarantelli’s, Charles Fritz, posited that “as social animals, people perhaps come closer to fulfilling their basic human needs in the aftermath of disaster than at any other time.”

Some 2,500 years ago, Gotama Buddha allegedly remarked that "the world is on fire... everything is burning," and used this as a basis for the elementary teachings of compassion and right action. Nowadays, between the climate crisis and its attendant "natural disasters" (not to mention systemic violence and militarism), it is increasingly evident how prescient those words were. And in moments of crisis like these wildfires, with our skies enshrouded in smoke, we can see how literally true the Buddha's words have become. One can only hope that, when the smoke clears, we remember that the world continues to smolder, calling forth our courage and kindness implicitly in times of peace just as it did explicitly in times of disaster.

As Solnit writes, “it's tempting to ask why, if you fed your neighbors during the time of the earthquake and fire, you didn't do so before or after.”

The Covid pandemic brings similar lessons and questions. By all means, this unifying crisis reminds us that humanity is one common family sharing a common planet and a common fate. When the crisis was most apparently acute in early 2020, there was a certain fellowship that was evident in our behavior, a sense that "we're in this together" — but as the months have worn on and as we've become inured to pandemic life and excited to return to "normal," this sentiment of oneness seems to have waned a bit. I pray that, to whatever extent a return to normalcy is even possible now, we take with us the lessons of unity and compassion that we began to learn during these challenging times.

On one of my trips up the smoldering mountain during the Valley Fire, I discovered that, luckily, my home had not burned down. The hamlet of Loch Lomond was saved by firefighters. In the ensuing weeks, however, the fire would inspire my landlord to sell the house I was renting, requiring me to move out a few months later and thus displacing me in slow motion.

In those weeks I spent as an evacuee and throughout the fire's immediate aftermath, I set aside the project of running for Congress. There was too much to do in the moment. With my normal reality disrupted, I experienced an almost superhuman ability to exist on very little sleep. Between my time in the radio booth and my work out in the field, I was an active part of the "civic immune response" Quarantelli described.

Along with some local allies, I continued to prepare for and publicize the upcoming "Hands Around Clear Lake" gathering and healing ceremony, an event we produced every year along the shores of the ancient lake, featuring an afternoon and evening of music and celebration followed by a sunrise ceremony with indigenous healers to honor the water and support our return to right relationship with our shared environment and each other.

It was actually on the day of Hands Around Clear Lake, September 26, over two weeks into the disaster, that the roads back up and over Cobb finally reopened, allowing thousands of us to return home at last (that is, those of us who had homes to return to at all). But the gathering still took place, and it was quite beautiful.

The audio quality isn't so great, but there is a video of the speech I gave at the fifth annual Hands Around Clear Lake, just as the news came in that many of us were free to return to our homes.

It wasn't until February, once much of the Valley Fires's ashen dust had literally settled, that I at last returned in earnest to the looming decision of whether to run for Congress.

The deadline to declare my candidacy was fast-approaching, and as far as I knew, no real progressive candidates had emerged to challenge our long-time, pro-war, "blue dog Democrat" incumbent, Mike Thompson. Nationally, Bernie's nascent presidential campaign continued to make waves and challenge the political establishment with its calls for social, racial, environmental and economic justice for all.

Then came a night I will never forget. I was up late, doing research on my computer in the Loch Lomond home that would soon be sold, requiring me to move. I had found my way to the Federal Election Commission website, which documents and shares publicly all financial contributions made to political candidates. And there I discovered the jarring truth that my "democratic" representative routinely accepted major campaign payouts from some of the worlds worst corporations — too-big-to-fail banks like Bank of America and Wells Fargo, telecom giants like Verizon and AT&T, Big Pharma outfits like Merck and Pfizer, weapons manufacturers like Raytheon and Honeywell, and fossil fuel companies like Tesoro, not to mention a bevy of health insurance goliaths, industrial agriculture monoliths, lobbyists from the alcohol industry, huge corporate real estate developers and more — year after year, giving Thompson millions of dollars to fund his easy reelection time and again.

It was no wonder this representative was not taking a meaningful stand on climate change, wage inequality, endless war, the health care crisis, or any of the number of woes we faced (and continue to face) as a country. He was in bed with the very companies that benefitted most from maintaining the status quo.

I thought about my daughter and future generations, and the world we will be passing on to them. I thought of those laboring and suffering under a strained and lopsided economy ever favoring the most wealthy and privileged. I thought of the already rampant police violence and other racist acts being perpetrated on people of color across this country. I thought of the countless uninsured and underinsured Americans dying (as my father did) deeply in medical debt. And I thought of this rich, white incumbent, seeking election to his ninth term, never having taken a bold stand on any of the pressing issues of our time.

That night, I decided that I would run.

Right after my declaration of candidacy (literally, the very night I threw a house party to celebrate the campaign's launch with friends and family), I found out my house was going to sell and that I had sixty days to move out.

That will have to be another story for another time — but if you're curious, my website and YouTube channel are both replete with artifacts of my 2016 and 2018 campaigns, from my platform and endorsements, to countless videosof my speeches, all begging to be integrated as I continue about the joyful task of sharing my story.

For now, I'll conclude on this sweet and hopeful note.

I mentioned that, when the Valley Fire began, my dog Spirit had been missing for weeks. As the fire raged on, I thought she was a goner for sure.

Then, in April, just a few days before I moved out (ultimately completing my campaign on the road, with my things in storage), I received a call from Animal Control.

They had found Spirit.

Thankfully, this little critter had been microchipped. Somehow, she had found her way to a furniture store in Lakeport. She was wearing a strange collar, looking ragged and underweight. But she was alive — and apparently just as stoked to see me as I was to see her.

Little Toot eventually became my mom's dog, enjoying an active (if somewhat spoiled) retirement in Pacifica until her death this April, the same day Derek Chauvin was convicted of murdering George Floyd. You can read her eulogy here.

I wonder, is it a reach for me to claim that my post-fire reunion with my dog symbolizes how, during times of crisis, we are so often reunited with with our own "Spirit," a la A Paradise Built in Hell?

Perhaps so. Either way, this time of year — the newly dubbed "fire season" — often serves as a reminder for me, not only that the world we inhabit remains ablaze (whether visibly or not), but of the collective strength and resilience we possess, and the "altruistic, communitarian, resourceful and imaginative" alternative reality we are capable of creating together.

As always, I'm honored to be in community with you.

Much love and respect,

Nils

PS. While my recent dance with cancer and ongoing recovery were not the focus of this week's post, I continue to invite your support for my healing fundraiser. After my last email, we reached the milestone of being 2/3 of the way toward reaching our goal! Your ongoing support has been a real game-changer in helping me to cover medical costs and make ends meet through my recovery. Thank you!